What is attachment theory?

Attachment theory is based on the assertion that we are genetically wired to be in a close relationship because attachment increases our chances of survival. In short, we have a human need to bond. This need is even more important than eating. The theory was initially developed by British psychologist John Bowlby and was expanded upon by Mary Ainsworth’s “strange situation” experiment. The way in which we attach to others has been categorized into four attachment styles: secure, anxious, avoidant, and disorganized (or anxious/avoidant). Researchers estimate that around 50 percent of individuals are secure, 20 percent are anxious, 25 percent are avoidant, and the remaining 3 to 5 percent are anxious/avoidant.

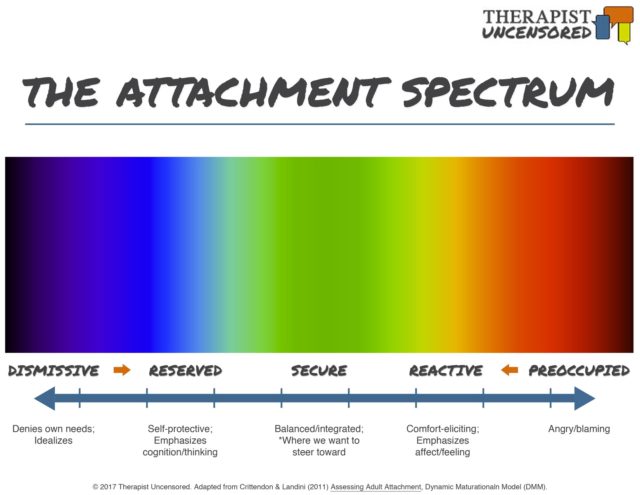

Note: Different theorists came up with different names for each attachment style basically to get credit for their work. Unfortunately, this makes labeling attachment styles a little confusing. For example, “anxious” is also known as “preoccupied” and “angry resistant”. The avoidant attachment style can also be known as “dismissive”. The disorganized attachment style is also known as “anxious/avoidant”.

Infant Attachment

The easiest way to picture attachment styles is probably to describe the strange situation experiment:

Children between the ages of 12 and 18 months are in a room playing with their mom, a stranger enters the room, the mom discreetly leaves the room, and then the mom returns to comfort the child. For any child, a little distress when the mom leaves the room is considered healthy. The attachment style was determined based on the child’s response to the mom coming back into the room.

These responses were categorized into the aforementioned attachment styles:

Secure- The baby was distressed when the mom leaves and comforted by the mom’s return. The baby uses mom as a secure base (or anchor) to explore in the room.

Anxious– The baby was intensely distressed when the mom leaves and runs towards the mom when she returns but is somewhat inconsolable and might even push the mom away. The baby cries more and explores less than the other participants.

Avoidant– The baby shows no outward signs of distress when the mom leaves (although might feel distressed internally) and ignores the mom when she comes back. The baby is comfortable exploring and is equally comfortable with the mom and stranger.

Adult Attachment

The attachment between parent and child has been studied and documented for a long time. What we now know is that the same theory can be applied to adult relationships, specifically between two romantic partners. The goal of couples therapy is essentially creating a more secure attachment between you and your partner. To get there, it’s helpful to first examine your current attachment style so that both of you can make sense of your own behavior and your partner’s.

As you continue to read, it’s most helpful to think of attachment styles on a continuum. For example, you might be securely attached to your partner most of the time but lean toward the anxious side of the continuum occasionally. It’s less important that you completely fit into one category and more important that you understand how and when you move on the continuum. Here is a visual originally developed by Austin therapists and creators of Therapist Uncensored, Dr. Ann Kelley and Sue Marriott.

A couple of notes about how this information is organized:

1) The disorganized or anxious/avoidant attachment style is usually associated with trauma–though we all have pockets of disorganization. This attachment style is equally important, but it is not described in detail in this article. I tend to think of the disorganized attachment style as a less predictable combination of the attachment styles described.

2) I am not claiming to or trying to reinvent the wheel with this information. I am simply trying to condense a theory that informs a lot of my work with clients into one easy-to-read post. I’ll include my sources at the bottom. Alright, here we go!

Secure Attachment Style

Secure attachment style (aka “green” or the “anchor”)– You enjoy being intimate without becoming overly worried about your relationships. You are interdependent in your relationships. You feel safe and secure in your relationships. You are comfortable openly and directly communicating your needs and feelings and are also able to read and respond to your partner’s cues.

The basic premise of a secure attachment between two partners is “you are there for me when I need you, and I am there for you when you need me”. The more confident you both feel in relying on each other and being relied upon, the more comfortable you feel with giving each other freedom to explore and be independent.

When I talk about attachment theory with couples, I talk a lot about attunement. Attunement is the rhythm couples develop when they are able to recognize and respond to each other’s needs consistently. There’s a certain element of predictability and healthy entitlement in secure relationships.

Building a secure attachment comes down to timing, attention, and presence. When one of you is in a vulnerable state or position, you are given a small window to respond appropriately. If you miss that window or you miss that window more times than you don’t, trust is broken. For example, if you see on your partner’s face that he or she had a bad day and you pretend not to notice (or you genuinely didn’t notice), you missed the opportunity to connect. In a secure relationship, partners see the window of opportunity and act on it.

Anxious Attachment Style

This attachment style is also known as preoccupied, “red”, or the “wave”. You love to be very close to your romantic partners and have the capacity for great intimacy. You often fear, however, that your partner does not wish to be as close as you would like him/her to be. You tend to be very sensitive to small fluctuations in your partner’s moods and actions, and although your senses are often accurate, you take your partner’s behaviors too personally. For example, you might misread a neutral facial expression as negative or interpret your partner’s silence as anger. You might also experience your partner’s emotions about something unrelated to you as directed at you.

What does it look like?

- Hyperactive or overactivation of the attachment system

- You are often angry at your partner and ambivalent about your relationship.

- You cling & seek or blame & push away at the same time.

- You often say things like “How could you do this to me?”.

- You find it very difficult to soothe your emotions internally.

- Your greatest fear in relationships is that if someone leaves, you will not be ok.

Common traits of someone that is anxiously attached: Indecisive, people-pleasing, fearful of the outside world or distrustful of outsiders, highly verbal—overtalks during a conflict.

Common protest behavior (excessive attempts to reestablish contact):

- Calling, texting, or emailing many times

- Obsessing about receiving a response

- Withdrawing

- Keeping score

- Acting hostile

- Threatening to leave

- Manipulations

- Acting out (or cheating) in an attempt to detach or make the other person jealous

How does this develop?

Initially, there was a misattunement between the parent and the baby/child. Either the parent’s timing was off or the parent misread what the child needed. The result was that the parent inconsistently provided hope and disappointment in the child’s times of need. The inconsistency of a parent’s response created hypervigilance for the child–the child was always on alert for how the parent is doing. The child might have also developed a preoccupation (an obsessive worry) about his or her relationship with the parent.

Ideally, parents would be calm, confident, and responsive to their child’s needs. Of course, this is easier said than done. Parents of anxiously attached children tend to be insecure, often fearful in their parenting. What happens is that when the child gets dysregulated, the parent becomes dysregulated. Since a child is entirely dependent on the parent for survival, he or she learns to attune to the parent instead of the parent attuning to him or her.

This type of parent generally does well when a child is afraid because the parent knows what that feels like. However, if the child wants to explore the parent might feel threatened or rejected (“Why don’t you love me?”) or fearful for the child’s safety (“the world is not safe”).

What to do if you have this attachment style:

Define yourself—be selfish! Have your own opinions, make your own decisions, learn what pleases you. These are things that might have been overtly or covertly discouraged as a child but will serve you well as an adult.

Become more internal oriented (rather than external).

Increase curiosity and vigilance in how you are doing. Do a body scan.

For example, an externally oriented response might be something like, “Oh no, I think they’re mad at me” “Did I do that right?”. An internal oriented response might be something like, “Wow I’m really obsessing”.

Notice your own cues and situations that will activate you.

Name it to tame it—become aware of when you feel activated.

Learn to self-soothe. We can’t always look to someone else to soothe us.

Instead of saying, “I have to have you to calm down” or “I can’t calm down until you do this” try “I’m so angry. We’re gonna talk when I calm down”.

When activated, you might feel like you need to be right. What you really need is to self-soothe so you can feel heard/acknowledged. This suggestion can seem counterintuitive, but you might need to turn the volume down so your partner can hear you. Instead of getting louder and bigger when you feel unheard, try waiting until you feel calm enough to talk at a level your partner can hear you. You can also gauge when your partner is ready to listen to you. Your partner will not hear you if he or she is feeling flooded.

What to do if your partner has this attachment style:

Take your partner seriously, but stay really calm and don’t overreact. When you see your partner is hyperactivated, go towards them softly. Think of how you approach a scared, stray dog (but don’t be condescending). Encourage (but don’t push) your partner to develop his or her sense of self. Have compassion, knowing that protest behavior often comes from an involuntary place of fear.

Goal: Secure attachment. You want to move more towards having a clear sense of self. You want to be able to give your partner the benefit of the doubt when you’re feeling activated and refrain from spinning out as often.

Avoidant Attachment Style

This attachment style is also known as dismissive, “blue” or the “island”. It is very important for you to maintain your independence and self-sufficiency and you prefer autonomy to intimate relationships. Even though you want to be close to others, you feel uncomfortable with too much closeness and tend to keep your partner at arm’s length. In relationships, you are often on high alert for any signs of control or impingement on your territory. For example, you might enjoy spending a lot of time alone or with friends and you might not notice when the quality time between you and your partner has decreased. You might also feel suffocated when you spend too much time with your partner or experience your partner’s attempts to get closer to you as a threat to your individuality.

What does it look like?

- The attachment system is deactivated—the idea of needing a relationship in an interdependent way has become too threatening.

- You have become more of a singular system.

- In times of conflict, you lean out of the relationship (“I don’t need you”).

- You hide your desire for closeness.

- You get defensive during arguments, “What am I supposed to do?”. You find it difficult to accept your needs and your partner’s need for emotional connection.

- You are emotionally “zipped up”.

- Your relational needs are harder to identify because you are not as in tune with them.

- You don’t complain as much as your partner.

- Your greatest fear in relationships is a loss of self.

Common traits

- Highly independent

- Less focused on relationships, more focused on self

- Super confident in self (but can’t understand why other people are so clingy)

- Think more than feel (overemphasis on intellect to disconnect a feeling state)

Common deactivation strategies (ways to keep your partner at arm’s length)

- Fear of commitment—but staying together nonetheless, sometimes for years

- Focusing on small imperfections in your partner

- Pining after a fantasized ex

- Flirting with others

- Sending mixed signals—not saying “I love you” but implying that you do

- Pulling away when things are going well

- Forming relationships with an impossible future (someone married or long distance)

- “Checking out mentally” when your partner is talking to you

- Keeping secrets and leaving things foggy

- Avoiding physical closeness—not wanting to have sex, walking several strides ahead of your partner

How does this develop?

With this attachment style, there is often a history of maternal rejection, particularly related to negative emotions. It could be that the parent was depressed or wasn’t nurtured themselves and didn’t know how to respond to the child’s needs. If the infant cried, the parent got uncomfortable. Instead of outwardly showing dysregulation as evident with the anxious parent, the avoidant parent inhibits facial expression and physical affection. Thus, the infant learned it’s not ok to have big emotions.

This parent is somewhat the opposite of what the anxiously attached child experienced. This child was encouraged to explore and play with outsiders, and exploration was rewarded with affection. If the child was needy or dependent, however, the parent distanced him or herself. What the child learns is that big emotions push the parent (and people) away. Therefore, the child learns to deactivate emotions and needs to maintain a connection with the parent.

Researchers have found that babies with this attachment style tend to scoot next to their mother with their backs turned because they want to be close, but not too close to push the mother away. As adults, this is similar to the partner that invites you to an event, but wants to maintain a certain distance while you’re there!

What’s interesting about this attachment style is that an individual’s physical affect/facial expressions might not match his or her internal experience. For example, what might look like someone is disinterested could actually mean that he or she is so flooded with emotion they’ve gone into more of a frozen state. A blank face is hard to read and it’s easy to assign meaning that isn’t accurate so it’s important to talk about what you observe.

What to do if you have this attachment style:

Move more toward an interpersonal realm.

Develop the ability to need and depend on other people. Instead of saying, “I’m good on my own”, “Why do we need to do this?”, or rolling your eyes, try activating your needs and accepting help.

Might have to deconstruct idealization of “happy childhood”.

Increase your curiosity about relationships as a child and what might have been missing.

Connect to your emotions and attachment system.

Freely (visibly and verbally) express emotions. Often when individuals first activate these needs, it can be overwhelming. Individuals tend to go from avoidantly attached to a little anxiously attached before getting to secure.

What to do if your partner has this attachment style:

Keep trying to reach them, they do need you. Know that his/her feeling of being invaded might not have anything to do with you, BUT reach out in a non-threatening way. Don’t demand they pay attention to you, plant the seed. For example instead of saying, “Do this now” try “When do you think you might be ready?”.

Goal: Secure attachment. Turn towards someone during times of distress. You need human connection just as much as anyone else. You can still be alone and independent at times, but you can transition to interdependence with more ease.

Why is knowing your attachment style important and how can you work with attachment theory in therapy?

Attachment theory is not intended to blame, shame, label, or limit individuals and parents. Rather, attachment theory provides a framework for understanding how you relate to the people closest to you based on the first relationship you ever had. Learning about your attachment style can be painful at times. It’s hard to look back at your relationship with your primary caregiver and see something new for the first time or to revisit this relationship if you’ve wanted to gloss over it.

However, this work is so important because our attachment styles are largely unconscious. We respond intensely to certain scenarios and form patterns in relationships without knowing why. We also internalize a lot of “shoulds” about how independent and dependent we should be in relationships without realizing it. Creating awareness of your attachment style empowers you to reclaim any needs you disowned during childhood, to have agency in selecting and attaching to the right partner, and to move towards more secure relationships.

Sources:

Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How it Can Help You Find–and Keep–Love

Good Life Project with Stan Tatkin: Danger, Deviance and Conflict

2 comments

Heidi Helm

July 17, 2019 at 11:31 am

Amazing summary of attachment theory! Thank you. I am sharing this on my social media posts, as I really feel like this information, if made common knowledge, can help make the world a better place a billion times over. I know that for myself, my life has improved dramatically since learning about this, because my issues seem less like a character flaw, and more about my “programming” which can be changed with patience and practice. I have also found that a mindfulness and somatic exercices have been key in helping me reconnect to my viscera, which I had largely tuned out. When we push away critical information, we cannot use it to understand our deepest needs and desires, that can lead us towards an authentic and fulfilling life.

Alex Barnette

September 9, 2019 at 4:13 pm

Thanks for sharing, and I completely agree! Attachment theory offers a much less pathologizing way of viewing ourselves and our relationships. Mindfulness and somatic experiencing are also really great ways to tune in, especially since so much of what we react to is unconscious. Wishing you the best on your journey!